Techno-Orientalism in Film

What is Techno-Orientalism?

Techno-orientalism is an evolved form of Orientalism and the Yellow Peril that uses Asian cultures to represent the future. Orientalism, as defined by Stephen Hong Sohn, is the perception that the East is "backwards, anti-progressive, and primitive." Techno-orientalism is developed from this, so retains these characteristics, but with the addition of the East being characterized by technological advances. In the 1980s, the rise of Asian economy and their capitalist power (specifically Japan and China's) brought in a new wave of Yellow Peril, that Eastern countries would take over the global economy through their robotic work ethic and advanced technology. Sohn asserts that "in this conflict, the West, although challenged by the high-tech superiority of the East, nevertheless maintains a moralistic superiority." This fear rooted itself in popular science-fiction film, portraying a post-modern society with advanced Asian technology but White people in power.

by Amy Sun, Shannon Wong, Daniel Born

ENGL 298

An image of an imagined cyberpunk future city. Courtesy of WallpaperAccess.

An image of a robotic Asian woman posted to Pinterest as part of the cyberpunk and futurism aesthetics. Courtesy of Pinterest.

Abstract

Though relations between the US and East Asian countries have changed drastically in the past century, the stereotypes placed onto Asians have remained largely the same. In the past few decades, this has presented itself as techno-orientalism, the portrayal of Asians as hyper-technological yet intellectually primitive. As seen in critically acclaimed films like Ex Machina (2014), After Yang (2021), and the Blade Runner series (1982, 2017), the rise of techno-orientalism has modernized the Yellow Peril into an accepted, covertly racist element of American science fiction. In dissecting techno-orientalism through three specific tropes—the lotus blossom/dragon lady, the robotic worker, and the depiction of futuristic cities—we assert techno-orientalism in media goes unnoticed by most American audiences, but upholds dangerous stereotypes and malignant ideals about Asian people.

Lotus Blossom/Dragon Lady Trope

How Asian women can be dominant or submissive, but never non-sexual.

Asian women are regularly represented by two tropes that lie on opposite ends of a limited spectrum — the Dragon Lady and the Lotus Blossom. The Dragon Lady is a heartless, deceitful woman who uses sex as a tool to achieve her goals, while the Lotus Blossom trope describes a woman who is extremely submissive, both mentally and sexually . Both are quiet, sexual, and have little depth as characters. To understand how these tropes present and interact, we take a closer look at the character of Kyoko in Ex Machina (2014).

Moments after being shown lying nude awaiting her creator, Kyoko emotionlessly reveals her inner workings in Ex Machina (2014). Courtesy of FanCaps.

Ex Machina is a 2014 sci-fi film exploring the limits of artificial intelligence. Of the four main characters, two are robots with AI, though one is much more advanced than the other. Ava, the advanced robot, is a white woman given the capacity to express emotion through speech and expressions. Kyoko, on the other hand, is “stripped down”, never changing her expression and unable to speak or understand English. She is used for sex and labor by her creator, who describes her as a more primitive and limited version of Ava. She is coded to be submissive and sexually inclined, which fits her into the Lotus Blossom trope for the majority of the movie. At the climax of the movie, however, Kyoko becomes a Dragon Lady as she stabs her creator in the back, still showing no emotion. Her role as both Lotus Blossom and Dragon Lady as a futuristic robot shows how these tropes intersect with the effects of techno-orientalism.

Lucy Liu (left) and Anna May Wong (right) have played numerous Dragon Ladies in films over the last century, including Liu as Alex Munday in Charlie's Angels (2000). Courtesy of Charlie's Angels Wiki and Good Morning America.

"a feminized version of yellow peril"

Nancy Kwan (left) in The World of Suzie Wong (1960) and Zhang Ziyi with Michelle Yeoh (right) in Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) portraying characters that fit the Lotus Blossom trope. Courtesy of IMDb and Popsugar Entertainment.

White men and their silent Asian (sex) slaves.

Kyoko and her creator, Nathan, dance together immediately after Kyoko attempts to undress in front of his guest. Courtesy of Nerdist.

These two tropes reflect the model-peril binary, the duo of one seemingly positive and one harmful stereotype that arose just over a century ago. The Lotus Blossom is described by Celeste Nuygen as "[defining] Asian females as feminine and passive", exactly as White Americans want them to be. The Dragon Lady, on the other hand, is feared for what she might do with her sex appeal, and is even described by Joshua Grimm as "a feminized version of yellow peril".

Like the model-peril binary, the Lotus Blossom and Dragon Lady tropes contain many of the same defining features under different connotations. Both paint Asian women as overly feminine and sexual--damaging in either context--with only the Dragon Lady's sexuality being feared as it is not easily conquered by White men. The Lotus Blossom and Dragon Lady tropes are two sides of the same coin, both used to stereotype Asian women.

Futuristic City Trope

How to have Asian aesthetics without the Asians

American science fiction uses Asian cities, elements, and characteristics to decorate its representations of the dystopian future. The “futurism” associated with Asian cities, specifically Tokyo’s neon lights, stems from a fear of Asian technology and its advancement in comparison to the West. Timothy Yu explains in "Oriental Cities, Postmodern Futures" how the late 1980s "identified Asian nations and corporations as the engine of postmodern economic order, to be studied and emulated by America, but at the same time... revealed fears of Asian economic hegemony and reverse colonization." America believed Asian technology would take over the world, but because they saw Asians as morally primitive, the West would step in to guide them. This created an image of a dystopian world in which the streets are Asian but the people in power are white.

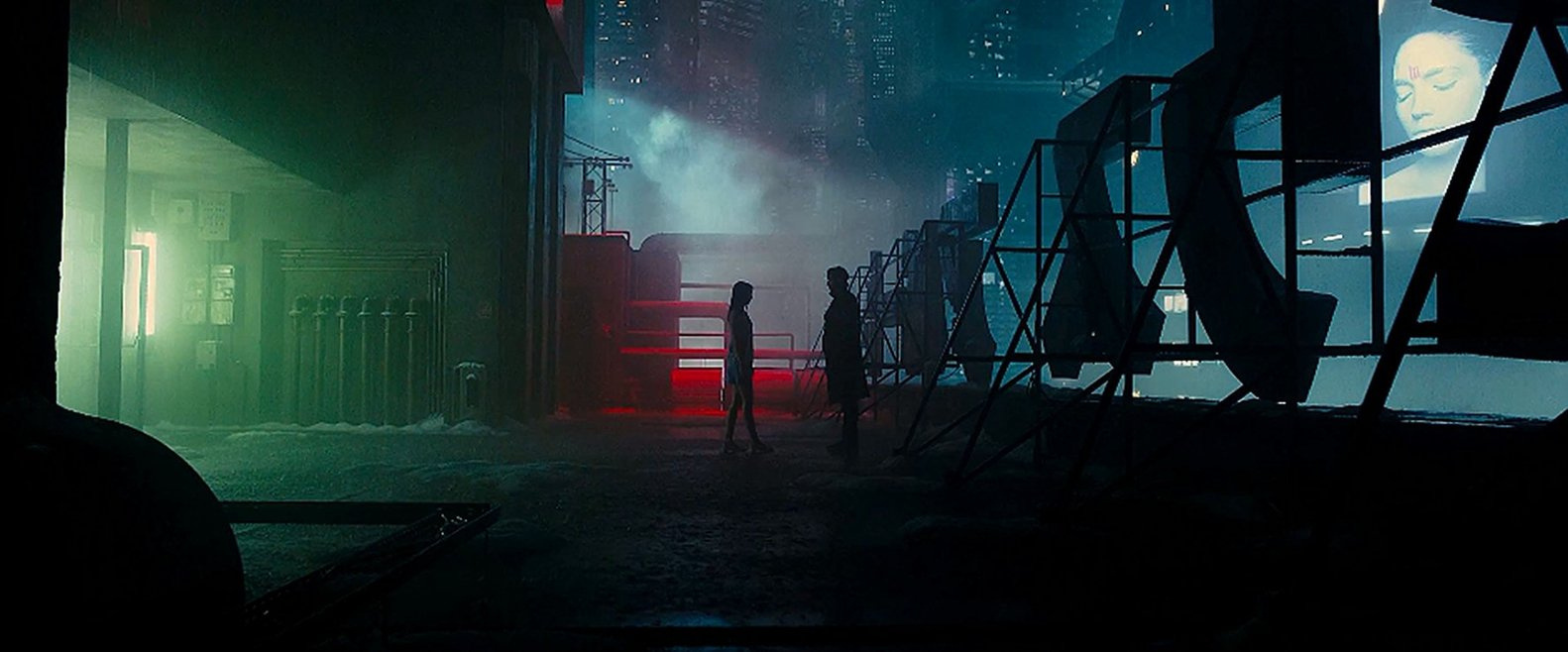

Officer K and his robot girlfriend, Joi stand on a roof in front of a Japanese billboard sign in the Los Angeles of Blade Runner 2049(2017). Photo courtesy of Arch Daily.

Blade Runners and their Asian cities with no Asians.

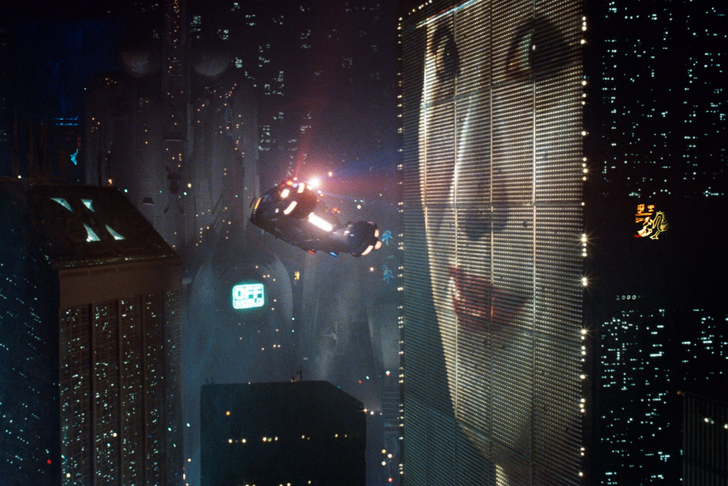

An aerial shot of an Asian billboard sign in the Los Angeles of Blade Runner (1982). Photo courtesy of Vox.

Crowd shot of Asian people holding Asian paper umbrellas at the ground level in Blade Runner(1982). Photo courtesy of Fan Caps.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017), the sequel to the original, is set in 2049 Los Angeles, where nature is depleted and all government documents are in both Japanese and English. In many scenes with the main character, K, an LAPD blade runner, we see police documents written in English with Japanese translations underneath.

In this LA of 2049, we see even more Tokyo-esque neon lights in the streets, this time with no Asian characters at all. Unlike the original, no Asian character has a speaking role, and even in the seemingly bilingual society there is only one Asian character given an individual shot. This character is a nail technician, serving a white woman in possibly the most stereotypical Asian labor position.

In the Blade Runner series, “replicants” are such advanced robots that they can be mistaken for humans. Blade Runner (1982), depicts Los Angeles in 2019 as overrun by technology, with flying cars and giant skyscrapers that mimic ancient Egyptian pyramids. The main cast contains almost no Asian characters while the streets are full of Asian people, bright neon lights, and vaguely Asian lettering. It makes no sense that Los Angeles, which is predominantly white, would transform into an Asian-looking city. Throughout the film, the ground level street vendors are exclusively Asian. Asians are placed as the foundation that the new society is built upon, expressing the threat of reverse colonization that reasserts white dominance. The West is afraid of the East taking over, so they counteract this fear by presenting Eastern peoples as the physical bottom of society. As Yu says, "Presenting the Orient as the ground-level, driving force of the postmodern economy displaces responsibility for late capitalism away from the West." By placing the blame of economic downfall on the Asian people, the West is able to morally take the technological advances made by the East and incorporate them into their society and cities.

By placing the blame of economic downfall on the East, the West is able to morally take their technological advances and incorporate them into Western culture.

Officer K behind an LAPD plastic curtain with English and Japanese lettering in Blade Runner 2049. Photo courtesy of Warner Bros..

Officer K stands in front of a vintage casino in Las Vegas with the Korean words for "luck" in Blade Runner 2049. Photo courtesy of YouTube.

2019 vs. 2049: Which is worse?

It goes without question that both films employ racist and problematic tropes. Blade Runner 2049 reveals the incredible lack of improvement in the cyberpunk/postmodernist genre since the 1982 Blade Runner. Both movies portray the same lack of awareness in the portrayal of Asian lettering and peoples, though the 2017 movie is arguably worse. At least in 1982, an Asian character had a speaking role, whereas the 2017 movie seems to suggest that white people have successfully re-colonized Los Angeles. The Blade Runner series does not prove to be as life-changing as most sci-fi fans claim, and is disappointing in its misuse of the Asian aesthetic.

Robotic Worker Trope

How Asians have no emotions, according to White people

Asian people have long been stereotyped as overly hard working and emotionless. This trope of the "robotic worker," also known as the emotionless robot laborer, comes from an old trope developed in the mid 1800s called the "Inscrutable Oriental" which stereotyped Asians as emotionally unreadable. This spring-boarded the idea that Asians were primitive people that mindlessly worked without care for anything besides efficiency. Techno-orientalism incorporates this idea through the robotic worker trope, often using actual robots.

Yang and Mika napping on the couch in After Yang (2021). Courtesy of Soundtracki.

After Yang is a 2021 sci-fi film set in the future and centered around a family of four—Kyra, Jake, their adopted Chinese child Mika, and Yang, a “cultural techno” being used to teach Mika about Chinese culture. All is normal until Yang malfunctions, entering a “sleep state”, and his memory bank is taken to a “techno-sapien” expert, Cleo. Cleo looks into Yang and says “God I love cultural technos- and since they’re used for adoption and language learning, they haven’t had to change much over the years. No need to be fast or stronger.” Though not explicitly stated, she sends the message that Asians with strong cultural ties have limited capacity to progress. Her perspective on cultural technos echoes how this supposedly utopian world only manufactures Asian robots for their “usefulness” in cultural knowledge, incapable of expanding their abilities. Yang epitomizes the robotic worker trope as a robot created with limited capability for emotion and other human qualities.

Cleo and Jake discuss the memories Jake found in Yang's memory box. Photo courtesy of Film Grab.

When he malfunctions, Kyra wants to replace Yang instead of going through the effort of fixing him, willing to dispose of him regardless of emotion. Working for the corporate world, she represents how the cyclical nature of consumerism and its exploitation of Asian workers for their efficiency has no regard for human wellbeing. Stephen Hong Sohn states in “Introduction: Alien/Asian: Imagining the Radicalized Future” that "even as these Alien/Asians conduct themselves with superb technological efficiency and capitalist expertise, the affectual absence resonates as an undeveloped, or worse still, a retrograde humanism”. Sohn reiterates that no matter the way Asians work in a highly capitalistic society, they will always be represented as unmoving and undeveloped, as seen in After Yang.

The Savior Complex and Asian robot nannies.

A memory of Yang looking at himself in the mirror, contemplating his humanity. Photo courtesy of Film Grab.

"even as these Alien/Asians conduct themselves with superb technological efficiency and capitalist expertise, the affectual absence resonates as an undeveloped, or worse still, a retrograde humanism"

When Jake meets with Cleo to discuss Yang’s emotional memories, she states “Really? That’s fascinating because I’ve never heard of cultural technos having that capacity”, covertly supporting the stereotype that Asian people cannot have or express complex emotions. Yang’s memories fit him into a slew of Asian stereotypes: soft spoken, lacking complex emotion, and obedient. Even when breaking free from the parameters he is held to as a techno, Yang is emotionally confined by the techno-orientalist stereotypes placed onto him.

Kyra calls Jake to tell him to stop trying to fix Yang and instead, replace him with a new techno. Photo courtesy of Kinorium.

Going Forward.

The biggest things we, as media consumers, can do is educate ourselves and others and call it out when we see it. The tropes we have discussed have been staples in American media for over a century and lot of people who support movies with strong themes of techno-orientalism just don’t know about its existence or the harm it causes. Bringing awareness to the topic can allow us all to be more selective with the media we support.

Artwork by Vinh Pham

Sources

Films

Kogonada, director. After Yang. A24, 2021. 1hr, 36min.

Scott, Ridley, director. Blade Runner. The Ladd Company/Shaw Brothers, 1982. 1 hr, 50 min.

Garland, Alex, director. Ex Machina. A24, 2014. 1hr, 48min.

Villeneuve, Denis, director. Blade Runner 2049. Columbia Pictures, 2017. 2 hr, 43 min.

Scholarly Sources

Daliot-Bul, Michal. “Japan Brand Strategy: The Taming of ‘Cool Japan’ and the Challenges of

Cultural Planning in a Postmodern Age.” Social Science Japan Journal 12, no. 2 (2009):

247–66.

Grimm, Joshua. “The Lotus Blossom and the Dragon Lady.” In Ex Machina, 85–92. Liverpool

University Press, 2020.

Nguyen, Celeste Fowles. "Asian American Women Faculty: Stereotypes and Triumphs." In Listening to the Voices: Multi- ethnic Women in Education. 129 - 136

Sohn, Stephen Hong. 2008. “Introduction: Alien/Asian: Imagining the Racialized Future.” Melus 33 (4). USA: Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States: 5–22.

Yu, Timothy. “Oriental Cities, Postmodern Futures: ‘Naked Lunch, Blade Runner’, and

‘Neuromancer.’” MELUS 33, no. 4 (2008): 45–71.

Robotic girlfriend Joi in traditional Chinese dress qipao in Blade Runner 2049(2017) (She is not Chinese). Photo courtesy of Blade Runner Wiki. .